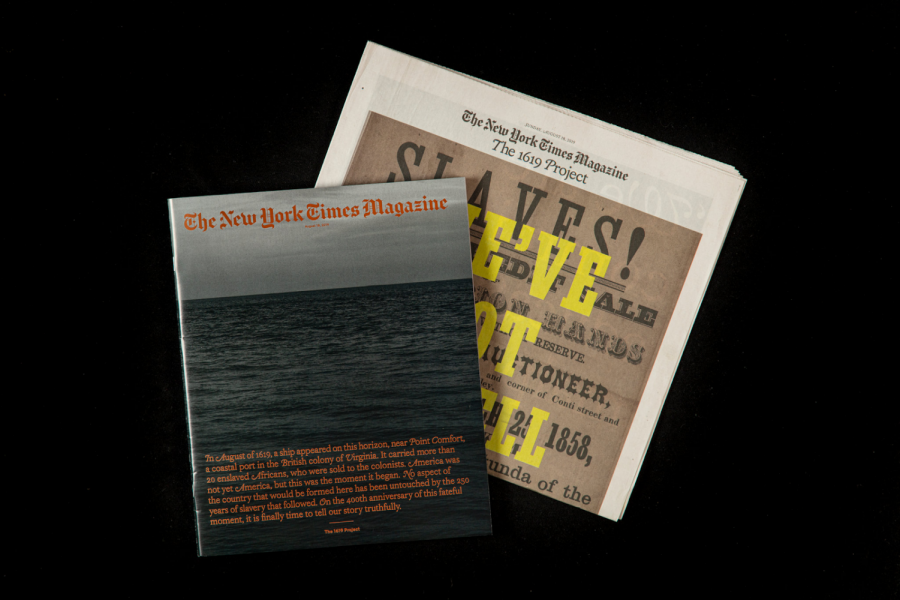

A Legacy of Debate: The 1619 Project

April 29, 2021

Created by New York Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones, the 1619 Project is a long-form journalism series, podcast, and set of curriculum materials (produced by the Pulitzer Center). Individually or in collaboration, they aim to teach the history of the United States with a goal of illuminating and focusing in on our nation’s roots in slavery.

Since its inaugural episode and publication in August 2019, the Project has generated controversy and rebuttal — from conservative media personalities, esteemed historians, and Republican politicians (including then-President Donald Trump) alike.

Despite pushback, the project still has garnered acclaim and support in the form of wide distribution of the curriculum in five school systems (New York; Chicago; Buffalo; Washington DC; Wilmington, Delaware; Winston-Salem, North Carolina), broad support from teachers and professors, and a Pulitzer Prize for Hannah-Jones. In 2019, Vice President Kamala Harris voiced her support as well.

The first episode (the whole podcast is available online here) opens with a consideration of the place the first ship carrying slaves—called the White Lion—docked. It’s followed by a personal anecdote from Hannah-Jones.

“When I was a child, my dad always flew a flag in our front yard,” Hannah-Jones recounts. “Our house is on a corner lot, and in the front yard right in the corner was this — I couldn’t tell you how tall it was. It always seemed really garishly tall to me at the time. There was this very tall aluminum flagpole.”

This introductory story exemplifies the theme of placing stories of modern Black patriotism alongside what she sees as America’s clear legacy– one of racism, oppression, and hate.

Hannah-Jones goes on to examine and discuss the Constitution, juxtaposing the document and the idyllic principles that supposedly guided our country’s founding with the horrors of slavery and the brutal battle for civil rights.

The podcast and printed series work through the history of slavery, oppression and civil rights for Black Americans chronologically, mixing modern considerations of identity and systematic racism with historic counterparts and struggles.

“This essay was about democracy and the unparalleled role that Black Americans have played almost always without getting credit and actually creating the democracy that we have, and making those glorious words of the declaration actually true for all Americans,” said Hannah-Jones, summarizing the Project in an NPR interview following her Pulitzer win.

Despite the project’s 2019 release, prominent political controversy over it only arose more recently. In July of 2020, Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) introduced a bill called the “Saving American History Act of 2020,” seeking to ban the project from all US public schools.

“The New York Times’ 1619 Project is a racially divisive, revisionist account of history that denies the noble principles of freedom and equality on which our nation was founded,” said Cotton. The act was read on the Senate floor, but was never voted on.

More recently, three bills were introduced by state legislators in Iowa, Mississippi, and Arkansas, each banning use of the curriculum in their own states’ schools rather than the whole nation. As state governments, not the Federal government, control curriculum, these challenges pose more of a question to the future of the Project in schools.

On January 18th, 2021, former President Trump issued a statement announcing a “1776 Commission,” which was formed in direct opposition to the New York Times’ 1619 Project with the goal of creating a “patriotic education,” according to the then-President.

Called “a dispositive rebuttal of reckless ‘re-education’ attempts that seek to reframe American history around the idea that the United States is not an exceptional country but an evil one,” in the statement, the Commission ceased work following Trump’s departure from office. Outside of its 46-page flagship report, the Commission never created any further curriculum or material.

While arguments have been cleanly divided in the political field, with most Democrats standing behind the Project and most Republicans opposing it, viewpoints of historians have been more varied.

“On August 19 of last year,” begins a Politico opinion piece written by Leslie M. Harris, professor of history at Northwestern University, “I listened in stunned silence as Nikole Hannah-Jones, a reporter for the New York Times, repeated an idea that I had vigorously argued against with her fact-checker…”

The opinion piece goes on to explain Harris’ main issue with the Project—the claim that the patriots fought the American Revolution to preserve slavery in America—which she had cited (since the New York Times asked for her review of the Project before its publication) as being “overstated.”

However, Harris still stands by the message key to the Project and much of its controversies:

“Overall, the 1619 Project is a much-needed corrective to the blindly celebratory histories that once dominated our understanding of the past—histories that wrongly suggested racism and slavery were not a central part of U.S. history,” wrote Harris.

Similar criticism came from five prominent historians, who wrote a letter to New York Times Editor-in-Chief Jake Silverstein criticizing the Times’ fact-checking process, citing claims they called “distorted” and “misleading.”

“Raising profound, unsettling questions about slavery and the nation’s past and present, as The 1619 Project does, is a praiseworthy and urgent public service,” reads the letter to the Times, which was published by the paper in December of 2020. “Nevertheless, we are dismayed at some of the factual errors in the Project and the closed process behind it.”

The letter concludes with a request that the Times issue “prominent corrections of all the errors and distortions presented in the 1619 Project,” and remove “these mistakes from any materials destined for use in schools, as well as in all further publications…”

Alongside the letter’s publication was a response from Silverstein, which rebutted claims of major error and distortion.

“While we welcome criticism, we don’t believe that the request for corrections to the 1619 Project is warranted,” writes Silverstein. “We are not ourselves historians, it is true. We are journalists, trained to look at current events and situations and ask the question: Why is this the way it is? In the case of the persistent racism and inequality that plague this country, the answer to that question led us inexorably into the past—and not just for this project.”

Going on to cite prominent historians whose claims supported those of the Project as well as examining the historical events Hannah-Jones based her own claims off of, Silverstein’s response ultimately denies the request for correction.

“Though we may disagree on some important matters, we are grateful for their input and their interest in discussing these fundamental questions about the country’s history,” it ends.

However, the primary claim disputed by Harris and one of those cited by the five historians in their letter was updated on March 11th, 2020 in a clarification published by the Times almost 8 months following the publication of the essay.

“If the scholarship of the past several decades has taught us anything, it is that we should be careful not to assume unanimity on the part of the colonists…” wrote Silverstein. “We recognize that our original language could be read to suggest that protecting slavery was a primary motivation for all of the colonists. The passage has been changed to make clear that this was a primary motivation for some of the colonists.”

In a piece titled “Ideology Over Excellence: Awarding the Pulitzer Prize to the 1619 Project,”attorney and author Patricia Barnes writes that the essay was “well reasoned or compelling”, claiming it was ultimately undeserving of its Pulitzer, in part due to the previously mentioned correction following the print publication.

She also suggests the seven member jury that selected Hannah-Jones’s piece was “stacked”, both due to the race of jury members, which skewed African-American, and some jury members’ affiliation or former affiliation with the New York Times.

In a 2019 opinion piece published by Vox, author J. Brian Charles defended the Project against attacks by conservative personalities such as Newt Gingrich, who called the essay and podcast “propaganda.” Specifically, Charles confronted “some conservatives [that] are upset that black journalists are leading narratives on race and reexamining history.”

Charles also cited a tweet by New York Times politics reporter Astead W. Herndon, saying: “the narrative is often that black writers are somehow non-objective opinion activists for including race in political conversation, deeply reported projects like 1619 are reminders that it’s the inverse—to ignore race—that is the non-journalistic, activist position.”

Though published more than a year and a half ago at the time of writing, debate over the Project is still ongoing with countless opinion and commentary pieces published and written across all news media platforms, often with contradicting pieces published by the same publication.

“I believe most Americans will seek exceptionalism and American unity over guilt, divisiveness and a racial definition of our history. The New York Times failed with its Trump-Russian project, and now it is going to fail with its “racist America” project,” ends Newt Gingrich’s opinion piece on the project.

“It is easy to correct facts; it is much harder to correct a worldview that consistently ignores and distorts the role of African-Americans and race in our history in order to present white people as all powerful and solely in possession to the keys of equality, freedom and democracy,” ends Prof. Leslie M. Harris’s piece. “At least that is the corrective history toward which the 1619 Project is moving, if imperfectly.”