Ute Canyon Trail in Colorado National Monument

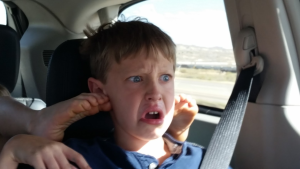

View of Ute Canyon from Liberty Cap Trail.

May 11, 2021

Colorado National Monument is a land of gorgeous canyon country. Soaring walls, tall spires, arches, and more characterize the landscape here, all locked within deep, red rock canyons. Near the southern edge of the monument lies Ute Canyon, a long, open gorge which contains all of these natural features. The trail through this canyon is unmaintained, which adds to the solitude felt when hiking in this majestic landscape. With all this being said, let’s get into it.

Begin the hike by switchbacking down off of the rim. Compared to other trails in the monument, the route down to the bottom of the canyon is actually quite well built, with little to no exposure found along the entire section. Once at the bottom of the canyon, the route enters a wash. Wondrous views abound, with tall, desert cliffs soaring high above the valley floor.

About a half mile away lies Fallen Rock, a huge chunk of rock that slid off the side of the canyon. The USGS says “Fallen Rock illustrates the geologic processes that are shaping the landscape at Colorado National Monument. Fallen Rock is a block of Wingate Sandstone that split away from the cliff where Ute Creek had undercut the softer shaly sediments of the Chinle Formation along the creek bed. More erosion will eventually break down the great block into sediments to be carried away by water.”

When walking under it, the rock towers above the landscape, and makes any hiker feel small and insignificant. From here, the route scoots up and out of the wash and onto a scree bench. This sudden elevation gain is made in order to avoid the narrows of the wash, which cut through the Precambrian Granite that makes up the floor of the canyon.

This Precambrian Granite has a completely different texture and toughness to it in comparison to the surrounding cliffs, which is fairly odd. When looking at Colorado National Monument from Grand Junction, the red rock cliffs appear to sit on top of a table of sorts. This table is completely made out of granite, and creates an odd clash between the soft, malleable sandstone and the tough, nearly indestructible granite. Why does the monument look like this? Three words: The Great Unconformity.

In geology, different rock layers come from different time periods. Wingate Sandstone, for example, comes from an era 192-206 million years ago. This Sandstone makes up most of the monument’s cliffs. Underneath it is the Chinle Formation, which was formed 220-206 million years ago. This formation is the crumbly, dark red rock that makes up the base of the monoliths and walls that characterize the monument. These two layers are close to each other, and make sense geologically. And then, the bright desert sandstone suddenly disappears, giving way to the previously mentioned black granite. The difference in between the rocks is quite odd, but even odder is the time difference. How big is this time difference? Oh, not large at all, just a mere 1.5 BILLION YEARS.

This insane time difference is The Great Unconformity, and it is one of the most puzzling things that geologists have to deal with when figuring out the geologic story of many places. The law of superposition states, generally, layers below other layers are older. In the case of The Great Unconformity, this holds true. The only problem, though, is the massive time difference. Geologists don’t really have an explanation for this, as it quite literally appears as if millions, (sometimes billions) of years of geologic time have just disappeared. This, of course, isn’t true, and theories are being made every day trying to explain the bizarre phenomenon. With this being said, The Great Unconformity doesn’t just occur only in Colorado National Monument. In fact, it can be found all over the world, and this just causes further confusion, making one ponder the nature of reality itself.

Continue on the trail, scooting back down into the wash. From here, it’s about 5 miles to the lower Wildwood Trailhead. The route to the lower trailhead follows along the bottom of the canyon, passing by a couple of great rock outcroppings which, if climbed onto, give great views down the lengthy canyon.

The cliffs tower high above the valley floor and make for a cool background when walking down the route. The occasional overgrowth of plants can be found, but the trail is actually quite easy to follow, despite what the signs may say. After 3-4 miles, you eventually reach the mouth of the canyon, marking the end of the sandstone and the beginning of the descent down to the lower trailhead.

A turn-off is soon reached. In front of you lies the connecting route over to the liberty cap trail, and to the right of you lies the corkscrew trail. Take a right.

Starting down the corkscrew trail, the terrain instantly becomes rockier with steep, vertical cliffs blocking easy access to the grand valley far below. The route scoots alongside these cliffs for a while, before suddenly disappearing off the edge. A sharp switchback is taken, and then the calm, meandering nature of the previous segments is lost, instead being replaced with constant, never-ending “corkscrew” switchbacks, relentlessly cutting through the granite, ever so slowly losing elevation over time. These switchbacks were built by John Otto, the park’s first caretaker. And my god, did he know how to build a trail.

The endless switchbacks eventually come to an end, giving way to a nice, chill path that makes its way over to the trailhead. Behind you lies the precambrian bench that the park sits on top of. It’s quite the view, with The Great Unconformity being in full display. Take one final glance back at the canyons, and then have a buddy take you back to your car. If not, you’ll have to hike back.

Final Thoughts

Ute Canyon is a beautiful and spectacular canyon in the heart of Colorado National Monument. Remember to bring a friend, always tell somebody where you’re headed, and watch out for flash floods. Finally, have fun! This is a really beautiful trail in a spectacular canyon.